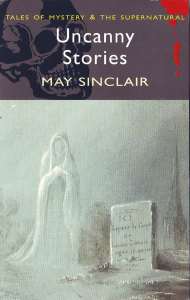

Uncanny Stories by May Sinclair (1923, Wordsworth, 2006)

Last year I was very ill. I was able to keep working but I didn’t get out much. One of the ways I dealt with this was to revisit my first literary love, tales of the supernatural. I’ll basically take anything, but my favourites are Victorian and Edwardian.

This is a life-long obsession. My late mother was a Spiritualist and I grew up in an environment in which readings and séances were as natural as church and football, although my father dismissed such things as ‘Codswallop!’ To this day I remain fascinated with the subject, and still a little afraid of ghosts. Anyway, however ill or down I was last year I could always get completely lost in a short, scary story. I have a lot of anthologies in the house, and I worked through all of them, saving a battered and much loved copy of the complete M.R. James for last. When I finished this I was bereft. Contemporary short stories and horror fiction did not have the same palliative effect. Then, one afternoon my wife rang from a discount shop in the city. She’d found a selection of Wordsworth ‘Tales of Mystery & The Supernatural’ for a pound a pop, did I want any?

This was a treasure trove, and I’m really writing to commend the whole series, most of which are still available. These are beautiful editions, anthologies of 19th and early-20th century short stories of murder, ghosts or both by the likes of J.S. Le Fanu, William Hope Hodgson, Guy Boothby and Amelia B. Edwards which I’m assuming are now mostly out of copyright. There are even collected penny dreadfuls I would’ve killed to own when I was doing my doctorate in the 90s, such as Wagner the Werewolf by the wonderful G.W.M. Reynolds. There are scholarly introductions and bibliographies, and the book design is lush. The covers are slate grey with well chosen artwork, clean typography, and embossed with a skull and dripping blood, feeling at once contemporary and gothic.

The collection that really put the hook in me, however, was May Sinclair’s Uncanny Stories, which I’m ashamed to say I had never previously read. If you have not read the work of this remarkable woman either then treat yourself. Her stories at once combine the late-romantic tradition with the conceptual experimentation of the early-modernists, as if Emily Brontë had collaborated with Virginia Woolf.

The collection that really put the hook in me, however, was May Sinclair’s Uncanny Stories, which I’m ashamed to say I had never previously read. If you have not read the work of this remarkable woman either then treat yourself. Her stories at once combine the late-romantic tradition with the conceptual experimentation of the early-modernists, as if Emily Brontë had collaborated with Virginia Woolf.

May Sinclair (Mary Amelia St. Clair, 1863 – 1946) was a suffragette and in her day a significant literary critic who counted among her friends Ezra Pound, Hilda Doolittle and the war poet Richard Aldington. Although her name is not often included in the modernist pantheon, she coined a term synonymous with the movement, ‘the stream of consciousness.’ Her sensitivity to the interior monologue, as literature at the cutting edge absorbed Freudian theory and challenged representational art, is perfectly expressed in her ‘uncanny’ stories (a term borrowed from Freud). In these stories the psychological and the paranormal merge, with an undercurrent of repression and desire, doubly damned through class and gender.

‘Die? We have died. Don’t you know what this is? Don’t you know where you are? This is death. We’re dead, Harriott. We’re in hell!’ – Where Their Fire Is Not Quenched

There’s a kind of Manichean mysticism to these things, in which magic might well exist, only in a very bleak, if not downright hostile universe. These are intelligent shockers and I don’t want to spoil them, but I’ll just say that in ‘Where their Fire is not Quenched’ hell is drenched in sex in the worst kind of way (decades before Clive Barker), while in ‘The Token’ the death of unrequited desire is not the end. ‘The Flaw in the Crystal’ is a powerful exploration of the toll mental illness takes on its carers; ‘If the Dead Knew’ is Freud meets M.R. James; while ‘The Victim’ isn’t perhaps what you’d expect. ‘The Finding of the Absolute’ offers a glimpse of a modernist afterlife, and the collection concludes with a masterpiece about which I will say nothing called ‘The Intercessor.’ On that note, excellent though Dr. Paul March-Russell’s introduction to this edition is, don’t read it until after the stories because he does give away some of the punch lines.

Ghost stories are like fairy tales, inasmuch as there’s a definite formula to the things, which is why they drift in and out of fashion, however culturally endemic. Like Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the Folk Tale you can generally predict the structure and outcome, rather like an EC horror story: girl meets boy; boy murders girl’s husband; husband comes back as a vengeful revenant; murders girl and boy… you know what I mean. In Sinclair’s stories you have no idea what’s coming. They clearly indicate a turning point in the genre, but like her literary criticism they are not as well known (at least outside academia) as they deserve to be, although there is a May Sinclair Society.

Ghost stories are like fairy tales, inasmuch as there’s a definite formula to the things, which is why they drift in and out of fashion, however culturally endemic. Like Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the Folk Tale you can generally predict the structure and outcome, rather like an EC horror story: girl meets boy; boy murders girl’s husband; husband comes back as a vengeful revenant; murders girl and boy… you know what I mean. In Sinclair’s stories you have no idea what’s coming. They clearly indicate a turning point in the genre, but like her literary criticism they are not as well known (at least outside academia) as they deserve to be, although there is a May Sinclair Society.

These stories are a must for anyone interested in modernism, early-feminism, and/or who just loves a good ghost story. They remain original and fresh, leaving one wishing, among other things, that contemporary authors of supernatural film and fiction looked to sources like this rather than just copying each other’s movies. Read May Sinclair alone and after dark and enjoy the pleasing terror.

Reblogged this on The Official Green Door Design for Publishing WordPress Blog.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for the recommendation! I can’t wait to get my hands on this book!

LikeLike

I have this book but I haven’t read it yet. This post bumps it a little higher up on my TBR.

LikeLike

i like this…

saludos..

att: Mailly Mejia R .. i´m From Ecuador

LikeLike